mirror of

https://github.com/bootdotdev/fcc-learn-golang-assets.git

synced 2025-12-10 15:21:18 +00:00

first

This commit is contained in:

12

README.md

12

README.md

@@ -1,2 +1,10 @@

|

||||

# fcc-learn-golang-assets

|

||||

A snapshot of the assets for the Learn Go course on FreeCodeCamp's youtube

|

||||

# Assets for "Learn Go" on FreeCodeCamp

|

||||

|

||||

This is a snapshot of the code samples for the ["Learn Go" course](https://boot.dev/courses/learn-golang) on [Boot.dev](https://boot.dev) at the time the video for FreeCodeCamp was released on YouTube. If you want the most up-to-date version of the code, please visit the official [Boot.dev course](https://boot.dev/courses/learn-http). Otherwise, if you're looking for the files used in the video, you're in the right place!

|

||||

|

||||

* [Course code samples](/course)

|

||||

* [Project steps](/project)

|

||||

|

||||

## License

|

||||

|

||||

You are free to use this content and code for personal education purposes. However, you are *not* authorized to publish this content or code elsewhere, whether for commercial purposes or not.

|

||||

|

||||

9

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/code.go

Normal file

9

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

// single-line comments start with "//"

|

||||

// comments are just for documentation - they don't execute

|

||||

fmt.Println("hello world")

|

||||

}

|

||||

9

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/complete.go

Normal file

9

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/complete.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

// single-line comments start with "//"

|

||||

// comments are just for documentation - they don't execute

|

||||

fmt.Println("starting Textio server")

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

starting Textio server

|

||||

11

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/readme.md

Normal file

11

course/1-intro/exercises/1-learn_to_run_code/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

||||

# Welcome to "Learn Go"

|

||||

|

||||

*This course assumes you're familiar with programming basics. If you're new to coding check out our [Learn Python course](https://boot.dev/learn/learn-python) first.*

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Booting up the "Textio" server

|

||||

|

||||

All the code you write in this course is part of a larger product: an SMS API called "Textio". Textio sends text messages over the internet, it's basically a cute Twilio clone.

|

||||

|

||||

Assignment: log `starting Textio server` to the console instead of `hello world`.

|

||||

22

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/code.go

Normal file

22

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,22 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

messagesFromDoris := []string{

|

||||

"You doing anything later??",

|

||||

"Did you get my last message?",

|

||||

"Don't leave me hanging...",

|

||||

"Please respond I'm lonely!",

|

||||

}

|

||||

numMessages := float64(len(messagesFromDoris))

|

||||

costPerMessage := .02

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch above this line

|

||||

|

||||

totalCost := costPerMessage + numMessages

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Printf("Doris spent %.2f on text messages today\n", totalCost)

|

||||

}

|

||||

22

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/complete.go

Normal file

22

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/complete.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,22 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

messagesFromDoris := []string{

|

||||

"You doing anything later??",

|

||||

"Did you get my last message?",

|

||||

"Don't leave me hanging...",

|

||||

"Please respond I'm lonely!",

|

||||

}

|

||||

numMessages := float64(len(messagesFromDoris))

|

||||

costPerMessage := .02

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch above this line

|

||||

|

||||

totalCost := costPerMessage * numMessages

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Printf("Doris spent %.2f on text messages today\n", totalCost)

|

||||

}

|

||||

1

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/expected.txt

Normal file

1

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/expected.txt

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

Doris spent 0.08 on text messages today

|

||||

5

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/readme.md

Normal file

5

course/1-intro/exercises/2-bug/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,5 @@

|

||||

# Fix a Bug!

|

||||

|

||||

Textio users are reporting that we're billing them for wildly inaccurate amounts. They're *supposed* to be billed `.02` dollars for each text message sent.

|

||||

|

||||

**Fix the math bug on line 17.**

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Go code generally runs ____ than interpreted languages and compiles ____ than other compiled languages like C and Rust",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"faster, faster",

|

||||

"faster, slower",

|

||||

"slower, faster",

|

||||

"slower, slower"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

11

course/1-intro/exercises/3-compiling_xkcd/readme.md

Normal file

11

course/1-intro/exercises/3-compiling_xkcd/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

||||

# Go is fast, simple and productive

|

||||

|

||||

Generally speaking, compiled languages run much faster than interpreted languages, and Go is no exception.

|

||||

|

||||

Go is one of the fastest programming languages, beating JavaScript, Python, and Ruby handily in most benchmarks.

|

||||

|

||||

However, Go code doesn't *run* quite as fast as its compiled Rust and C counterparts. That said, it *compiles* much faster than they do, which makes the developer experience super productive. Unfortunately, there are no swordfights on Go teams...

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

*- comic by [xkcd](https://xkcd.com/303/)*

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Does Go generally execute faster than Rust?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"No",

|

||||

"Yes"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

21

course/1-intro/exercises/4-lang_compare_speed/readme.md

Normal file

21

course/1-intro/exercises/4-lang_compare_speed/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,21 @@

|

||||

# Comparing Go's Speed

|

||||

|

||||

Go is *generally* faster and more lightweight than interpreted or VM-powered languages like:

|

||||

|

||||

* Python

|

||||

* JavaScript

|

||||

* PHP

|

||||

* Ruby

|

||||

* Java

|

||||

|

||||

However, in terms of execution speed, Go does lag behind some other compiled languages like:

|

||||

|

||||

* C

|

||||

* C++

|

||||

* Rust

|

||||

|

||||

Go is a bit slower mostly due to its automated memory management, also known as the "Go runtime". Slightly slower speed is the price we pay for memory safety and simple syntax!

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Textio is an amazing candidate for a Go project. We'll be able to quickly process large amounts of text all while using a language that is safe and simple to write.

|

||||

7

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/code.go

Normal file

7

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

fmt.Println("the-compiled Textio server is starting"

|

||||

}

|

||||

7

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/complete.go

Normal file

7

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/complete.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

fmt.Println("the-compiled Textio server is starting")

|

||||

}

|

||||

1

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/expected.txt

Normal file

1

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/expected.txt

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

the-compiled Textio server is starting

|

||||

17

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/readme.md

Normal file

17

course/1-intro/exercises/5-compiling_code/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

||||

# The Compilation Process

|

||||

|

||||

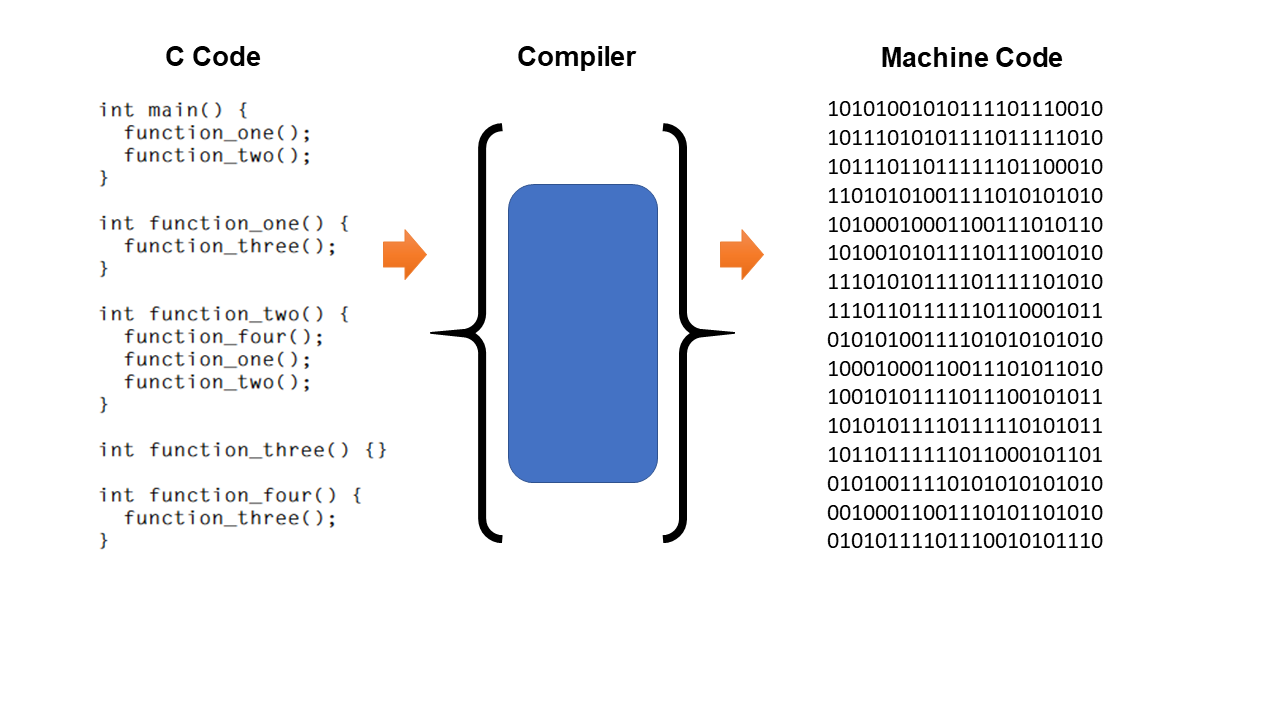

Computers need machine code, they don't understand English or even Go. We need to convert our high-level (Go) code into machine language, which is really just a set of instructions that some specific hardware can understand. In your case, your CPU.

|

||||

|

||||

The Go compiler's job is to take Go code and produce machine code. On Windows, that would be a `.exe` file. On Mac or Linux, it would be any executable file. The code you write in your browser here on Boot.dev is being compiled for you on Boot.dev's servers, then the machine code is executed in your browser as [Web Assembly](https://blog.boot.dev/golang/running-go-in-the-browser-with-web-assembly-wasm).

|

||||

|

||||

## A note on the structure of a Go program

|

||||

|

||||

We'll go over this all later in more detail, but to sate your curiosity for now, here are a few tidbits about the code.

|

||||

|

||||

1. `package main` lets the Go compiler know that we want this code to compile and run as a standalone program, as opposed to being a library that's imported by other programs.

|

||||

2. `import fmt` imports the `fmt` (formatting) package. The formatting package exists in Go's standard library and let's us do things like print text to the console.

|

||||

3. `func main()` defines the `main` function. `main` is the name of the function that acts as the entry point for a Go program.

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

To pass this exercise, fix the compiler error in the code.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Do computer processors understand English instructions like 'open the browser'?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"No",

|

||||

"Yes"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

33

course/1-intro/exercises/6-what_is_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

33

course/1-intro/exercises/6-what_is_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,33 @@

|

||||

# Compiling explained

|

||||

|

||||

Computers don't know how to do anything unless we as programmers tell them what to do.

|

||||

|

||||

Unfortunately computers don't understand human language. In fact, they don't even understand uncompiled computer programs.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, the code:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main(){

|

||||

fmt.Println("hello world")

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

means *nothing* to a computer.

|

||||

|

||||

## Computers need machine code

|

||||

|

||||

A computer's [CPU](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_processing_unit) only understands its own *instruction set*, which we call "machine code".

|

||||

|

||||

Instructions are basic math operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and the ability to save data temporarily.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, an [ARM processor](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARM_architecture) uses the *ADD* instruction when supplied with the number `0100` in binary.

|

||||

|

||||

## Go, C, Rust, etc.

|

||||

|

||||

Go, C, and Rust are all languages where the code is first converted to machine code by the compiler before it's executed.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Do users of compiled programs need access to source code?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"No",

|

||||

"Yes"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,24 @@

|

||||

# Compiled vs Interpreted

|

||||

|

||||

Compiled programs can be run without access to the original source code, and without access to a compiler. For example, when your browser executes the code you write in this course, it doesn't use the original code, just the compiled result.

|

||||

|

||||

Note how this is different than interpreted languages like Python and JavaScript. With Python and JavaScript the code is interpreted at [runtime](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runtime_(program_lifecycle_phase)) by a separate program known as the "interpreter". Distributing code for users to run can be a pain because they need to have an interpreter installed, and they need access to the original source code.

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of compiled languages

|

||||

|

||||

* Go

|

||||

* C

|

||||

* C++

|

||||

* Rust

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of interpreted languages

|

||||

|

||||

* JavaScript

|

||||

* Python

|

||||

* Ruby

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Why build Textio in a compiled language?

|

||||

|

||||

One of the most convenient things about using a compiled language like Go for Textio is that when we deploy our server we don't need to include any runtime language dependencies like Node or a Python interpreter. We just add the pre-compiled binary to the server and start it up!

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Which language is interpreted?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"Python",

|

||||

"Rust",

|

||||

"Go",

|

||||

"C++"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7a-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7a-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,24 @@

|

||||

# Compiled vs Interpreted

|

||||

|

||||

Compiled programs can be run without access to the original source code, and without access to a compiler. For example, when your browser executes the code you write in this course, it doesn't use the original code, just the compiled result.

|

||||

|

||||

Note how this is different than interpreted languages like Python and JavaScript. With Python and JavaScript the code is interpreted at [runtime](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runtime_(program_lifecycle_phase)) by a separate program known as the "interpreter". Distributing code for users to run can be a pain because they need to have an interpreter installed, and they need access to the original source code.

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of compiled languages

|

||||

|

||||

* Go

|

||||

* C

|

||||

* C++

|

||||

* Rust

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of interpreted languages

|

||||

|

||||

* JavaScript

|

||||

* Python

|

||||

* Ruby

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Deploying compiled programs is generally more simple

|

||||

|

||||

One of the most convenient things about using a compiled language like Go for Textio is that when we deploy our server we don't need to include any runtime language dependencies like Node or a Python interpreter. We just add the pre-compiled binary to the server and start it up!

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Why is it generally more simple to deploy a compiled server program?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"There are no runtime language dependencies",

|

||||

"Compiled code is faster",

|

||||

"Compiled code is more memory efficient",

|

||||

"Because docker exists"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7b-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

24

course/1-intro/exercises/7b-lang_compare_compiled/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,24 @@

|

||||

# Compiled vs Interpreted

|

||||

|

||||

Compiled programs can be run without access to the original source code, and without access to a compiler. For example, when your browser executes the code you write in this course, it doesn't use the original code, just the compiled result.

|

||||

|

||||

Note how this is different than interpreted languages like Python and JavaScript. With Python and JavaScript the code is interpreted at [runtime](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runtime_(program_lifecycle_phase)) by a separate program known as the "interpreter". Distributing code for users to run can be a pain because they need to have an interpreter installed, and they need access to the original source code.

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of compiled languages

|

||||

|

||||

* Go

|

||||

* C

|

||||

* C++

|

||||

* Rust

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples of interpreted languages

|

||||

|

||||

* JavaScript

|

||||

* Python

|

||||

* Ruby

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

## Why build Textio in a compiled language?

|

||||

|

||||

One of the most convenient things about using a compiled language like Go for Textio is that when we deploy our server we don't need to include any runtime language dependencies like Node or a Python interpreter. We just add the pre-compiled binary to the server and start it up!

|

||||

11

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/code.go

Normal file

11

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var username string = "wagslane"

|

||||

var password int = 20947382822

|

||||

|

||||

// don't edit below this line

|

||||

fmt.Println("Authorization: Basic", username+":"+password)

|

||||

}

|

||||

11

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/complete.go

Normal file

11

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/complete.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,11 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var username string = "wagslane"

|

||||

var password string = "20947382822"

|

||||

|

||||

// don't edit below this line

|

||||

fmt.Println("Authorization: Basic", username+":"+password)

|

||||

}

|

||||

1

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/expected.txt

Normal file

1

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/expected.txt

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

|

||||

Authorization: Basic wagslane:20947382822

|

||||

17

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/readme.md

Normal file

17

course/1-intro/exercises/8-strongly_typed/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

||||

# Go is Strongly Typed

|

||||

|

||||

Go enforces strong and static typing, meaning variables can only have a single type. A `string` variable like "hello world" can not be changed to an `int`, such as the number `3`.

|

||||

|

||||

One of the biggest benefits of strong typing is that errors can be caught at "compile time". In other words, bugs are more easily caught ahead of time because they are detected when the code is compiled before it even runs.

|

||||

|

||||

Contrast this with most interpreted languages, where the variable types are dynamic. Dynamic typing can lead to subtle bugs that are hard to detect. With interpreted languages, the code *must* be run (sometimes in production if you are unlucky 😨) to catch syntax and type errors.

|

||||

|

||||

## Concatenating strings

|

||||

|

||||

Two strings can be [concatenated](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concatenation) with the `+` operator. Because Go is strongly typed, it won't allow you to concatenate a string variable with a numeric variable.

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

We'll be using simple [basic authentication](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_access_authentication) for the Textio API. This is how our users will communicate to us who they are and how many features they are paying for with each request to our API.

|

||||

|

||||

The code on the right has a type error. Change the type of `password` to a string (but use the same numeric value) so that it can be concatenated with the `username` variable.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Generally speaking, which language uses more memory?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"Java",

|

||||

"Go"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

17

course/1-intro/exercises/9-lang_compare_memory/readme.md

Normal file

17

course/1-intro/exercises/9-lang_compare_memory/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

||||

# Go programs are easy on memory

|

||||

|

||||

Go programs are fairly lightweight. Each program includes a small amount of "extra" code that's included in the executable binary. This extra code is called the [Go Runtime](https://go.dev/doc/faq#runtime). One of the purposes of the Go runtime is to cleanup unused memory at runtime.

|

||||

|

||||

In other words, the Go compiler includes a small amount of extra logic in every Go program to make it easier for developers to write code that's memory efficient.

|

||||

|

||||

## Comparison

|

||||

|

||||

As a general rule Java programs use *more* memory than comparable Go programs because Go doesn't use an entire virtual machine to run its programs, just a small runtime. The Go runtime is small enough that it is included directly in each Go program's compiled machine code.

|

||||

|

||||

As another general rule Rust and C++ programs use slightly *less* memory than Go programs because more control is given to the developer to optimize memory usage of the program. The Go runtime just handles it for us automatically.

|

||||

|

||||

## Idle memory usage

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In the chart above, [Dexter Darwich compares the memory usage](https://medium.com/@dexterdarwich/comparison-between-java-go-and-rust-fdb21bd5fb7c) of three *very* simple programs written in Java, Go, and Rust. As you can see, Go and Rust use *very* little memory when compared to Java.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,9 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "What's one of the purposes of the Go runtime?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"To cleanup unused memory",

|

||||

"To compile Go code",

|

||||

"To style Go code and make it easier to read",

|

||||

"To cook fried chicken"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

17

course/1-intro/exercises/9a-lang_compare_memory/readme.md

Normal file

17

course/1-intro/exercises/9a-lang_compare_memory/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

||||

# Go programs are easy on memory

|

||||

|

||||

Go programs are fairly lightweight. Each program includes a small amount of "extra" code that's included in the executable binary. This extra code is called the [Go Runtime](https://go.dev/doc/faq#runtime). One of the purposes of the Go runtime is to cleanup unused memory at runtime.

|

||||

|

||||

In other words, the Go compiler includes a small amount of extra logic in every Go program to make it easier for developers to write code that's memory efficient.

|

||||

|

||||

## Comparison

|

||||

|

||||

As a general rule Java programs use *more* memory than comparable Go programs because Go doesn't use an entire virtual machine to run its programs, just a small runtime. The Go runtime is small enough that it is included directly in each Go program's compiled machine code.

|

||||

|

||||

As another general rule Rust and C++ programs use slightly *less* memory than Go programs because more control is given to the developer to optimize memory usage of the program. The Go runtime just handles it for us automatically.

|

||||

|

||||

## Idle memory usage

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In the chart above, [Dexter Darwich compares the memory usage](https://medium.com/@dexterdarwich/comparison-between-java-go-and-rust-fdb21bd5fb7c) of three *very* simple programs written in Java, Go, and Rust. As you can see, Go and Rust use *very* little memory when compared to Java.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,49 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func getFormattedMessages(messages []string, formatter func) []string {

|

||||

formattedMessages := []string{}

|

||||

for _, message := range messages {

|

||||

formattedMessages = append(formattedMessages, formatter(message))

|

||||

}

|

||||

return formattedMessages

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func addSignature(message string) string {

|

||||

return message + " Kind regards."

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func addGreeting(message string) string {

|

||||

return "Hello! " + message

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(messages []string, formatter func(string) string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

formattedMessages := getFormattedMessages(messages, formatter)

|

||||

if len(formattedMessages) != len(messages) {

|

||||

fmt.Println("The number of messages returned is incorrect.")

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

for i, message := range messages {

|

||||

formatted := formattedMessages[i]

|

||||

fmt.Printf(" * %s -> %s\n", message, formatted)

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Thanks for getting back to me.",

|

||||

"Great to see you again.",

|

||||

"I would love to hang out this weekend.",

|

||||

"Got any hot stock tips?",

|

||||

}, addSignature)

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Thanks for getting back to me.",

|

||||

"Great to see you again.",

|

||||

"I would love to hang out this weekend.",

|

||||

"Got any hot stock tips?",

|

||||

}, addGreeting)

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,49 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func getFormattedMessages(messages []string, formatter func(string) string) []string {

|

||||

formattedMessages := []string{}

|

||||

for _, message := range messages {

|

||||

formattedMessages = append(formattedMessages, formatter(message))

|

||||

}

|

||||

return formattedMessages

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func addSignature(message string) string {

|

||||

return message + " Kind regards."

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func addGreeting(message string) string {

|

||||

return "Hello! " + message

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(messages []string, formatter func(string) string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

formattedMessages := getFormattedMessages(messages, formatter)

|

||||

if len(formattedMessages) != len(messages) {

|

||||

fmt.Println("The number of messages returned is incorrect.")

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

for i, message := range messages {

|

||||

formatted := formattedMessages[i]

|

||||

fmt.Printf(" * %s -> %s\n", message, formatted)

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Thanks for getting back to me.",

|

||||

"Great to see you again.",

|

||||

"I would love to hang out this weekend.",

|

||||

"Got any hot stock tips?",

|

||||

}, addSignature)

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Thanks for getting back to me.",

|

||||

"Great to see you again.",

|

||||

"I would love to hang out this weekend.",

|

||||

"Got any hot stock tips?",

|

||||

}, addGreeting)

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,10 @@

|

||||

* Thanks for getting back to me. -> Thanks for getting back to me. Kind regards.

|

||||

* Great to see you again. -> Great to see you again. Kind regards.

|

||||

* I would love to hang out this weekend. -> I would love to hang out this weekend. Kind regards.

|

||||

* Got any hot stock tips? -> Got any hot stock tips? Kind regards.

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

* Thanks for getting back to me. -> Hello! Thanks for getting back to me.

|

||||

* Great to see you again. -> Hello! Great to see you again.

|

||||

* I would love to hang out this weekend. -> Hello! I would love to hang out this weekend.

|

||||

* Got any hot stock tips? -> Hello! Got any hot stock tips?

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,37 @@

|

||||

# First Class and Higher Order Functions

|

||||

|

||||

A programming language is said to have "first-class functions" when functions in that language are treated like any other variable. For example, in such a language, a function can be passed as an argument to other functions, can be returned by another function and can be assigned as a value to a variable.

|

||||

|

||||

A function that returns a function or accepts a function as input is called a Higher-Order Function.

|

||||

|

||||

Go supports [first-class](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/First-class_Function) and higher-order functions. Another way to think of this is that a function is just another type -- just like `int`s and `string`s and `bool`s.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, to accept a function as a parameter:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func add(x, y int) int {

|

||||

return x + y

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func mul(x, y int) int {

|

||||

return x * y

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// aggregate applies the given math function to the first 3 inputs

|

||||

func aggregate(a, b, c int, arithmetic func(int, int) int) int {

|

||||

return arithmetic(arithmetic(a, b), c)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main(){

|

||||

fmt.Println(aggregate(2,3,4, add))

|

||||

// prints 9

|

||||

fmt.Println(aggregate(2,3,4, mul))

|

||||

// prints 24

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

Textio is launching a new email messaging product, "Mailio"!

|

||||

|

||||

Fix the compile-time bug in the `getFormattedMessages` function. The function body is correct, but the function signature is not.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,8 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "What is a higher-order function?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"A function that takes another function as an argument",

|

||||

"A function with superior logic",

|

||||

"A function that is first in the call stack"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

# Why First-class and Higher-Order Functions?

|

||||

|

||||

At first, it may seem like dynamically creating functions and passing them around as variables adds unnecessary complexity. Most of the time you would be right. There are cases however when functions as values make a lot of sense. Some of these include:

|

||||

|

||||

* [HTTP API](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_API) handlers

|

||||

* [Pub/Sub](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publish%E2%80%93subscribe_pattern) handlers

|

||||

* Onclick callbacks

|

||||

|

||||

Any time you need to run custom code at *a time in the future*, functions as values might make sense.

|

||||

|

||||

## Definition: First-class Functions

|

||||

|

||||

A first-class function is a function that can be treated like any other value. Go supports first-class functions. A function's type is dependent on the types of its parameters and return values. For example, these are different function types:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func() int

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func(string) int

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Definition: Higher-Order Functions

|

||||

|

||||

A higher-order function is a function that takes a function as an argument or returns a function as a return value. Go supports higher-order functions. For example, this function takes a function as an argument:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func aggregate(a, b, c int, arithmetic func(int, int) int) int

|

||||

```

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,8 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "What is a first-class function?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"A function that is treated like any other variable",

|

||||

"A function that has been deemed most important by the architect",

|

||||

"A function that takes another function as an argument"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

# Why First-class and Higher-Order Functions?

|

||||

|

||||

At first, it may seem like dynamically creating functions and passing them around as variables adds unnecessary complexity. Most of the time you would be right. There are cases however when functions as values make a lot of sense. Some of these include:

|

||||

|

||||

* [HTTP API](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_API) handlers

|

||||

* [Pub/Sub](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publish%E2%80%93subscribe_pattern) handlers

|

||||

* Onclick callbacks

|

||||

|

||||

Any time you need to run custom code at *a time in the future*, functions as values might make sense.

|

||||

|

||||

## Definition: First-class Functions

|

||||

|

||||

A first-class function is a function that can be treated like any other value. Go supports first-class functions. A function's type is dependent on the types of its parameters and return values. For example, these are different function types:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func() int

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func(string) int

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Definition: Higher-Order Functions

|

||||

|

||||

A higher-order function is a function that takes a function as an argument or returns a function as a return value. Go supports higher-order functions. For example, this function takes a function as an argument:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func aggregate(a, b, c int, arithmetic func(int, int) int) int

|

||||

```

|

||||

47

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/3-currying/code.go

Normal file

47

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/3-currying/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,47 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"errors"

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

// getLogger takes a function that formats two strings into

|

||||

// a single string and returns a function that formats two strings but prints

|

||||

// the result instead of returning it

|

||||

func getLogger(formatter func(string, string) string) func(string, string) {

|

||||

// ?

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func test(first string, errors []error, formatter func(string, string) string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

logger := getLogger(formatter)

|

||||

fmt.Println("Logs:")

|

||||

for _, err := range errors {

|

||||

logger(first, err.Error())

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func colonDelimit(first, second string) string {

|

||||

return first + ": " + second

|

||||

}

|

||||

func commaDelimit(first, second string) string {

|

||||

return first + ", " + second

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

dbErrors := []error{

|

||||

errors.New("out of memory"),

|

||||

errors.New("cpu is pegged"),

|

||||

errors.New("networking issue"),

|

||||

errors.New("invalid syntax"),

|

||||

}

|

||||

test("Error on database server", dbErrors, colonDelimit)

|

||||

|

||||

mailErrors := []error{

|

||||

errors.New("email too large"),

|

||||

errors.New("non alphanumeric symbols found"),

|

||||

}

|

||||

test("Error on mail server", mailErrors, commaDelimit)

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,49 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"errors"

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

// getLogger takes a function that formats two strings into

|

||||

// a single string and returns a function that formats two strings but prints

|

||||

// the result instead of returning it

|

||||

func getLogger(formatter func(string, string) string) func(string, string) {

|

||||

return func(first, second string) {

|

||||

fmt.Println(formatter(first, second))

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func test(first string, errors []error, formatter func(string, string) string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

logger := getLogger(formatter)

|

||||

fmt.Println("Logs:")

|

||||

for _, err := range errors {

|

||||

logger(first, err.Error())

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func colonDelimit(first, second string) string {

|

||||

return first + ": " + second

|

||||

}

|

||||

func commaDelimit(first, second string) string {

|

||||

return first + ", " + second

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

dbErrors := []error{

|

||||

errors.New("out of memory"),

|

||||

errors.New("cpu is pegged"),

|

||||

errors.New("networking issue"),

|

||||

errors.New("invalid syntax"),

|

||||

}

|

||||

test("Error on database server", dbErrors, colonDelimit)

|

||||

|

||||

mailErrors := []error{

|

||||

errors.New("email too large"),

|

||||

errors.New("non alphanumeric symbols found"),

|

||||

}

|

||||

test("Error on mail server", mailErrors, commaDelimit)

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,10 @@

|

||||

Logs:

|

||||

Error on database server: out of memory

|

||||

Error on database server: cpu is pegged

|

||||

Error on database server: networking issue

|

||||

Error on database server: invalid syntax

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

Logs:

|

||||

Error on mail server, email too large

|

||||

Error on mail server, non alphanumeric symbols found

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

40

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/3-currying/readme.md

Normal file

40

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/3-currying/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,40 @@

|

||||

# Currying

|

||||

|

||||

Function currying is the practice of writing a function that takes a function (or functions) as input, and returns a new function.

|

||||

|

||||

For example:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

squareFunc := selfMath(multiply)

|

||||

doubleFunc := selfMath(add)

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(squareFunc(5))

|

||||

// prints 25

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(doubleFunc(5))

|

||||

// prints 10

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func multiply(x, y int) int {

|

||||

return x * y

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func add(x, y int) int {

|

||||

return x + y

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func selfMath(mathFunc func(int, int) int) func (int) int {

|

||||

return func(x int) int {

|

||||

return mathFunc(x, x)

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In the example above, the `selfMath` function takes in a function as its parameter, and returns a function that itself returns the value of running that input function on its parameter.

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

The Mailio API needs a very robust error-logging system so we can see when things are going awry in the back-end system. We need a function that can create a custom "logger" (a function that prints to the console) given a specific formatter.

|

||||

|

||||

Complete the `getLogger` function. It should `return` *a new function* that prints the formatted inputs using the given `formatter` function. The inputs should be passed into the formatter function in the order they are given to the logger function.

|

||||

91

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/code.go

Normal file

91

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,91 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

"sort"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

const (

|

||||

logDeleted = "user deleted"

|

||||

logNotFound = "user not found"

|

||||

logAdmin = "admin deleted"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

func logAndDelete(users map[string]user, name string) (log string) {

|

||||

user, ok := users[name]

|

||||

if !ok {

|

||||

delete(users, name)

|

||||

return logNotFound

|

||||

}

|

||||

if user.admin {

|

||||

return logAdmin

|

||||

}

|

||||

delete(users, name)

|

||||

return logDeleted

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

type user struct {

|

||||

name string

|

||||

number int

|

||||

admin bool

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(users map[string]user, name string) {

|

||||

fmt.Printf("Attempting to delete %s...\n", name)

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

log := logAndDelete(users, name)

|

||||

fmt.Println("Log:", log)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

users := map[string]user{

|

||||

"john": {

|

||||

name: "john",

|

||||

number: 18965554631,

|

||||

admin: true,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"elon": {

|

||||

name: "elon",

|

||||

number: 19875556452,

|

||||

admin: true,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"breanna": {

|

||||

name: "breanna",

|

||||

number: 98575554231,

|

||||

admin: false,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"kade": {

|

||||

name: "kade",

|

||||

number: 10765557221,

|

||||

admin: false,

|

||||

},

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println("Initial users:")

|

||||

usersSorted := []string{}

|

||||

for name := range users {

|

||||

usersSorted = append(usersSorted, name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

sort.Strings(usersSorted)

|

||||

for _, name := range usersSorted {

|

||||

fmt.Println(" -", name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

|

||||

test(users, "john")

|

||||

test(users, "santa")

|

||||

test(users, "kade")

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println("Final users:")

|

||||

usersSorted = []string{}

|

||||

for name := range users {

|

||||

usersSorted = append(usersSorted, name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

sort.Strings(usersSorted)

|

||||

for _, name := range usersSorted {

|

||||

fmt.Println(" -", name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

}

|

||||

91

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/complete.go

Normal file

91

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/complete.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,91 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

"sort"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

const (

|

||||

logDeleted = "user deleted"

|

||||

logNotFound = "user not found"

|

||||

logAdmin = "admin deleted"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

func logAndDelete(users map[string]user, name string) (log string) {

|

||||

defer delete(users, name)

|

||||

|

||||

user, ok := users[name]

|

||||

if !ok {

|

||||

return logNotFound

|

||||

}

|

||||

if user.admin {

|

||||

return logAdmin

|

||||

}

|

||||

return logDeleted

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

type user struct {

|

||||

name string

|

||||

number int

|

||||

admin bool

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(users map[string]user, name string) {

|

||||

fmt.Printf("Attempting to delete %s...\n", name)

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

log := logAndDelete(users, name)

|

||||

fmt.Println("Log:", log)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

users := map[string]user{

|

||||

"john": {

|

||||

name: "john",

|

||||

number: 18965554631,

|

||||

admin: true,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"elon": {

|

||||

name: "elon",

|

||||

number: 19875556452,

|

||||

admin: true,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"breanna": {

|

||||

name: "breanna",

|

||||

number: 98575554231,

|

||||

admin: false,

|

||||

},

|

||||

"kade": {

|

||||

name: "kade",

|

||||

number: 10765557221,

|

||||

admin: false,

|

||||

},

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println("Initial users:")

|

||||

usersSorted := []string{}

|

||||

for name := range users {

|

||||

usersSorted = append(usersSorted, name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

sort.Strings(usersSorted)

|

||||

for _, name := range usersSorted {

|

||||

fmt.Println(" -", name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

|

||||

test(users, "john")

|

||||

test(users, "santa")

|

||||

test(users, "kade")

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println("Final users:")

|

||||

usersSorted = []string{}

|

||||

for name := range users {

|

||||

usersSorted = append(usersSorted, name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

sort.Strings(usersSorted)

|

||||

for _, name := range usersSorted {

|

||||

fmt.Println(" -", name)

|

||||

}

|

||||

fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

}

|

||||

19

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/expected.txt

Normal file

19

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/expected.txt

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,19 @@

|

||||

Initial users:

|

||||

- breanna

|

||||

- elon

|

||||

- john

|

||||

- kade

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

Attempting to delete john...

|

||||

Log: admin deleted

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

Attempting to delete santa...

|

||||

Log: user not found

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

Attempting to delete kade...

|

||||

Log: user deleted

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

Final users:

|

||||

- breanna

|

||||

- elon

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

46

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/readme.md

Normal file

46

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/4-defer/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,46 @@

|

||||

# Defer

|

||||

|

||||

The `defer` keyword is a fairly unique feature of Go. It allows a function to be executed automatically *just before* its enclosing function returns.

|

||||

|

||||

The deferred call's arguments are evaluated immediately, but the function call is not executed until the surrounding function returns.

|

||||

|

||||

Deferred functions are typically used to close database connections, file handlers and the like.

|

||||

|

||||

For example:

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

// CopyFile copies a file from srcName to dstName on the local filesystem.

|

||||

func CopyFile(dstName, srcName string) (written int64, err error) {

|

||||

|

||||

// Open the source file

|

||||

src, err := os.Open(srcName)

|

||||

if err != nil {

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

// Close the source file when the CopyFile function returns

|

||||

defer src.Close()

|

||||

|

||||

// Create the destination file

|

||||

dst, err := os.Create(dstName)

|

||||

if err != nil {

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

// Close the destination file when the CopyFile function returns

|

||||

defer dst.Close()

|

||||

|

||||

return io.Copy(dst, src)

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In the above example, the `src.Close()` function is not called until after the `CopyFile` function was called but immediately before the `CopyFile` function returns.

|

||||

|

||||

Defer is a great way to **make sure** that something happens at the end of a function, even if there are multiple return statements.

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

There is a bug in the `logAndDelete` function, fix it!

|

||||

|

||||

This function should *always* delete the user from the user's map, which is a map that stores the user's name as keys. It also returns a `log` string that indicates to the caller some information about the user's deletion.

|

||||

|

||||

To avoid bugs like this in the future, instead of calling `delete` before each `return`, just `defer` the delete once at the beginning of the function.

|

||||

|

||||

46

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/5-closures/code.go

Normal file

46

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/5-closures/code.go

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,46 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func adder() func(int) int {

|

||||

// ?

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

type emailBill struct {

|

||||

costInPennies int

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(bills []emailBill) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

countAdder, costAdder := adder(), adder()

|

||||

for _, bill := range bills {

|

||||

fmt.Printf("You've sent %d emails and it has cost you %d cents\n", countAdder(1), costAdder(bill.costInPennies))

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{45},

|

||||

{32},

|

||||

{43},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{34},

|

||||

{54},

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{976},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{543},

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{743},

|

||||

{13},

|

||||

{8},

|

||||

})

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,50 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func adder() func(int) int {

|

||||

sum := 0

|

||||

return func(x int) int {

|

||||

sum += x

|

||||

return sum

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

type emailBill struct {

|

||||

costInPennies int

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func test(bills []emailBill) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

countAdder, costAdder := adder(), adder()

|

||||

for _, bill := range bills {

|

||||

fmt.Printf("You've sent %d emails and it has cost you %d cents\n", countAdder(1), costAdder(bill.costInPennies))

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{45},

|

||||

{32},

|

||||

{43},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{34},

|

||||

{54},

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{976},

|

||||

{12},

|

||||

{543},

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]emailBill{

|

||||

{743},

|

||||

{13},

|

||||

{8},

|

||||

})

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,17 @@

|

||||

You've sent 1 emails and it has cost you 45 cents

|

||||

You've sent 2 emails and it has cost you 77 cents

|

||||

You've sent 3 emails and it has cost you 120 cents

|

||||

You've sent 4 emails and it has cost you 132 cents

|

||||

You've sent 5 emails and it has cost you 166 cents

|

||||

You've sent 6 emails and it has cost you 220 cents

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

You've sent 1 emails and it has cost you 12 cents

|

||||

You've sent 2 emails and it has cost you 24 cents

|

||||

You've sent 3 emails and it has cost you 1000 cents

|

||||

You've sent 4 emails and it has cost you 1012 cents

|

||||

You've sent 5 emails and it has cost you 1555 cents

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

You've sent 1 emails and it has cost you 743 cents

|

||||

You've sent 2 emails and it has cost you 756 cents

|

||||

You've sent 3 emails and it has cost you 764 cents

|

||||

====================================

|

||||

37

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/5-closures/readme.md

Normal file

37

course/10-advanced_functions/exercises/5-closures/readme.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,37 @@

|

||||

# Closures

|

||||

|

||||

A closure is a function that references variables from outside its own function body. The function may access and *assign* to the referenced variables.

|

||||

|

||||

In this example, the `concatter()` function returns a function that has reference to an *enclosed* `doc` value. Each successive call to `harryPotterAggregator` mutates that same `doc` variable.

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func concatter() func(string) string {

|

||||

doc := ""

|

||||

return func(word string) string {

|

||||

doc += word + " "

|

||||

return doc

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator := concatter()

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mr.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("and")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mrs.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Dursley")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("of")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("number")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("four,")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Privet")

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(harryPotterAggregator("Drive"))

|

||||

// Mr. and Mrs. Dursley of number four, Privet Drive

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Assignment

|

||||

|

||||

Keeping track of how many emails we send is mission-critical at Mailio. Complete the `adder()` function.

|

||||

|

||||

It should return a function that adds its input (an `int`) to an enclosed `sum` value, then return the new sum. In other words, it keeps a running total of the `sum` variable within a closure.

|

||||

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "Can a closure mutate a variable outside its body?",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"Yes",

|

||||

"No"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,30 @@

|

||||

# Closure Review

|

||||

|

||||

A closure is a function that references variables from outside its own function body. The function may access and *assign* to the referenced variables.

|

||||

|

||||

## Example Closure

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func concatter() func(string) string {

|

||||

doc := ""

|

||||

return func(word string) string {

|

||||

doc += word + " "

|

||||

return doc

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator := concatter()

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mr.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("and")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mrs.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Dursley")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("of")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("number")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("four,")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Privet")

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(harryPotterAggregator("Drive"))

|

||||

// Mr. and Mrs. Dursley of number four, Privet Drive

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

{

|

||||

"question": "When a variable is enclosed in a closure, the enclosing function has access to ____",

|

||||

"answers": [

|

||||

"a mutable reference to the original value",

|

||||

"a copy of the value"

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,30 @@

|

||||

# Closure Review

|

||||

|

||||

A closure is a function that references variables from outside its own function body. The function may access and *assign* to the referenced variables.

|

||||

|

||||

## Example Closure

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func concatter() func(string) string {

|

||||

doc := ""

|

||||

return func(word string) string {

|

||||

doc += word + " "

|

||||

return doc

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator := concatter()

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mr.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("and")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Mrs.")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Dursley")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("of")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("number")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("four,")

|

||||

harryPotterAggregator("Privet")

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(harryPotterAggregator("Drive"))

|

||||

// Mr. and Mrs. Dursley of number four, Privet Drive

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,36 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func printReports(messages []string) {

|

||||

// ?

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func test(messages []string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

printReports(messages)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Here's Johnny!",

|

||||

"Go ahead, make my day",

|

||||

"You had me at hello",

|

||||

"There's no place like home",

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Hello, my name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.",

|

||||

"May the Force be with you.",

|

||||

"Show me the money!",

|

||||

"Go ahead, make my day.",

|

||||

})

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func printCostReport(costCalculator func(string) int, message string) {

|

||||

cost := costCalculator(message)

|

||||

fmt.Printf(`Message: "%s" Cost: %v cents`, message, cost)

|

||||

fmt.Println()

|

||||

}

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,40 @@

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func printReports(messages []string) {

|

||||

for _, message := range messages {

|

||||

printCostReport(func(m string) int {

|

||||

return len(m) * 2

|

||||

}, message)

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// don't touch below this line

|

||||

|

||||

func test(messages []string) {

|

||||

defer fmt.Println("====================================")

|

||||

printReports(messages)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Here's Johnny!",

|

||||

"Go ahead, make my day",

|

||||

"You had me at hello",

|

||||

"There's no place like home",

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

test([]string{

|

||||

"Hello, my name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.",

|

||||

"May the Force be with you.",

|

||||

"Show me the money!",

|

||||

"Go ahead, make my day.",

|

||||

})

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||